Applying design thinking to HR projects delivers fast results, but longer-term change needs a different approach. Teams require support and continual focus early on in the process to embed these new ways of working. Resources and effort must be focused on smaller groups for a sustained period of time to ensure success. This report outlines what HR can do differently to drive these behaviours and make them stick.

1. INTRODUCTION

I worked with Asahi Europe and International, a leading European beer company, between 2018 and 2022 as an Agile coach. The business is a regional market leader across Eastern and Western Europe, with high-profile, well-loved brands. Like many large corporations, decision-making and delivery on certain projects could be slow. The regional talent and learning director saw an opportunity to try a different way of working, led by the Human Resources teams.

Many multi-national organisations are heavily centralised, taking most decisions from a global hub. This organisation has distinct and separate in-country operating businesses. These separate, standalone companies have significant decision-making autonomy. The regional hub group has a significant influence on these companies but does not always have formal authority over them.

The work covered the application of Agile and design thinking methods to HR projects over four years and to increasing Agile capability within the whole business in this time period. Phase 1 focused on short sprints to solve specific HR regional problems; Phase 2 on training the HR function across Europe in Agile skills; Phase 3 on developing and implementing a company-wide Agile adoption program; Phase 4 on embedding these ways of working in other areas of the business outside of the HR function.

2. Background

As an Agile Coach, my approach is pragmatic, people-centered, and systemic, based on 20 years of experience in large multinationals. Earlier in my career as a global marketing manager, I was fascinated by the psychology of why people buy different brands. I was also intrigued (and sometimes frustrated) by how large companies were structured and operated. They often felt slow, unwieldy, and mechanistic.

From the marketing function, I became a learning and development manager, as well as a coach and facilitator, in my last corporate role. As an independent coach, I started with the Learning and Development team at Sky Media, a pioneer in Agile ways of working in HR. Some parts of Agile I knew well – design Thinking, and workshops – others were newer to me – iterative product development, transparency, and continuous improvement.

Seeing first-hand how this way of working could dramatically change how HR teams operated, I qualified as a Scrum master and Agile coach, learning from my mentor Natal Dank, co-author of AgileHR. The appeal was initially to speed up projects and make them more effective, delivering practical benefits to commercial businesses, which connected to my experience in marketing. On a deeper level, I saw how companies can work in more fulfilling ways and adapt more readily to change using Agile. It taps into deep human motivations (autonomy, control, purpose, desire to connect), leveraging them to release potential in people.

I know Asahi Europe and International well, first as an insider and then as an outsider. Before it was acquired by its current owner in 2017, it was the European arm of a global business called SAB Miller. I worked full-time for a larger company from 2012-2016. The current business has changed since becoming part of Asahi, but there are common cultural elements. Knowing the company well brings advantages and drawbacks: I know what is possible and how to get things done. Equally, I have biases and prejudices because I am closer to the business and its people than most external coaches would be.

3. INTRODUCING Agile to the business

3.1 Phase 1: Getting started with design sprints

In 2018, I discussed Agile ways of working and development with Geraldine Percival, the regional talent and learning Director. She thought it seemed promising but knew little about this way of working. Agile was completely new in the company, even for the digital teams.

Geraldine was an established and respected leader, having held many roles in the company. But progress on regional projects could be slow, with getting countries to work together often laborious. She thought a new approach might speed up decision-making and project delivery and also drive collaboration across countries on regional projects.

Developing a graduate recruitment program was selected as the best fit for an Agile experiment. First, it was a problem that clearly sat within the HR function, so it didn’t require formal agreements with other functions. Second, it was an urgent problem with real business consequences – it needed to be solved. Countries, especially Poland and Czechia, were struggling to recruit high-quality new starters. The marketplace for graduates has become more competitive, with many attractive companies now located in Prague and Warsaw. Graduate places were left unfilled, leading to the hiring of experienced managers instead at higher rates.

A multi-disciplinary team of 8 from 4 markets was formed, covering sales, marketing, HR, production, and finance. Members were selected to represent their function and whether the topic affected them. It was strictly voluntary – actively opting into the team.

The aim was to understand the problem in depth and develop a rough framework for a new graduate recruitment program. We chose to use this approach because it had been successful with Sky Media in my previous work. I was experienced in user-focused approaches from my marketing roles.

Using a design thinking approach, we followed these steps:

- A clear problem statement

- Interviewing users and developing user personas and journeys

- Developing and prioritizing ideas

- Creating a prototype and testing with users during the sprint.

- Reviewing the outputs in a showcase, and a retrospective

Over three days, the team worked on the challenge, split between Bucharest in Romania and Prague in Czechia, with five people at each location. This meant each sub-team worked for periods separately, then came together on teleconferences to review outputs and make changes. The output was a new strategy for graduate recruitment and development, based on evidence from the market and company and the region-wide framework, spanning a 5-year journey from graduate to senior manager.

The outputs met the stated goals. In the words of Catherine Sinclair, the regional HR Director:

‘I was blown away by the depth of insight….the range and level of recommendations…and the collaboration across countries. Amazing to see…how much the team created in a short period of time’

The team was exhausted but proud – there was a tangible energy in the room for the end review as they showcased their outputs.

Design Sprint 2

The second project aimed to overhaul the performance ratings process used across the region. This was the basis for evaluating employees annually and a key part of career progress. The 3-day exercise used the same approach and method as the graduate recruitment work (above) and tackled a much higher profile, wide-reaching subject because the rating process directly impacted bonus payments and pay rises for employees.

The output was a new region-wide, simplified performance ratings and bonus system. It was fairer and more connected to business goals, highlighting low and high performers more clearly. A key feature was a new bonus system that rewarded agreed company behaviours, as well as financial targets. Importantly the outputs met the needs of differing user groups across the company, avoiding one-size-fits-all.

Both sprints produced frameworks for new processes within HR. These frameworks then needed to be built out and implemented within the company. Implementation was classic waterfall: individuals making slower progress, reporting monthly, developing all the sections and finally launching it across the region.

Observations and Reflections from Phase 1

- The approach worked because it yielded quick results and brought together motivated individuals. They provided the structure for the people who were keen to collaborate.

- Based on the learning that people want opportunities and reasons to collaborate, if I were doing this again, I would create community forums and events straight away to connect more people across the company.

- We approached this as a one-off: understand the problem and develop a solution, which delivered short-term progress. Looking back from an organisational capability perspective, I would have tried to establish an ongoing Agile team, treating employee recruitment and retention as an ongoing product delivered by the HR function. Examples from other companies could be used to highlight the benefits of these teams.

- Having a multi-functional, multi-national group delivered user understanding and solutions that could work across multiple countries. The outputs weren’t seen as being ‘just from HR’, which led to faster acceptance – the ‘messengers’ were seen as credible because they came from within the business.

- User understanding and feedback seemed to be a critical success factor in the success of this initial phase. Team members’ perspectives changed once they interviewed users – seeing from other people’s perspectives produced an ‘Ah-ha’ moment of insight and highlighted the importance of emotion in decisions.

These collaborations demonstrated their value on complex projects – a one-week sprint delivered the work of 6 months using traditional processes, according to multiple internal stakeholders. The progress in such a short time period surprised us. The seed of Agile behaviours had been sown, and success in the company and demonstrated. Looking back, I see this was far from ongoing iterative delivery in teams – but we had started.

3.2 Phase 2: Building Agile skillsets and mindsets in HR

In spring 2020, the business experienced a huge shock. The Covid 19 pandemic shut down bars and dramatically reduced beer sales during successive lockdowns. This came only 4 months after the organisation had expanded to include Italy, The Netherlands and the UK considerably. For most of 2020, the business focused on keeping operations running, with most staff confined to their homes.

By Autumn 2020, Geraldine and Catherine, the regional HR Director, saw increased Agile skills and ways of working as useful to navigating this complexity and supporting the transformation of the business. By training the HR teams in these skills, they would be able to run their projects in Scrum teams, delivering faster and more effective solutions. I had recently started running a virtual AgileHR training program, created by Natal Dank and Riina Helstrom, authors of AgileHR.

The training built on the success of previous work in phase 1, allowing Agile enthusiasts from different countries to collaborate. Participants enjoyed working together on projects and helping each other. It allowed the HR function to be bold, curious and co-operative, 3 of the stated company values. It was pioneering – the first all-virtual program for the business.

Over 8 weeks, broken into 4 sections, we covered Agile ways of working, design thinking and application to their work. Participants worked on live, real business projects and applied their learnings in real time to the projects. Over the next 6 months, I trained 55 people, including all of the HR Directors and the regional head.

The participants experienced business value and problem framing; user centred approaches; iterative development; collaboration; and the Scrum framework. It resulted in all senior and many middle HR managers understanding key Agile principles, and many of them applied activities like stand-ups and retrospectives to everyday meetings.

Key outcomes

Throughout 2021, the HR function started to adopt the language of Agile and user focus, based on anecdotal feedback. Many were much more focused customers and users. Many – but not all – participants applied this user focus in their work, and tried to find ways to collaborate more with their colleagues. Most did not have the confidence to run these teams on their own – but a few did.

Individuals outside the HR function also joined the third and final program. They came from a broad range of other roles: procurement, transformation, finance and digital development. At the time, I saw this as positive evidence of demand outside of HR. However, they were outliers within their function, and had lower levels of application of the tools and concepts compared to HR teams. I believe this was because their peers didn’t understand Agile and the changes needed to work this way.

In the same period, I worked with the Polish part of the business to tackle a company-wide, strategic, wicked problem: how to maintain sales of returnable bottles in one part of the market, while growing share with their competitors in another part of the market. This stretched the design sprint approach to breaking point, running 5 virtual teams of 5 people across 2 periods of 3 days. ‘At times it was chaotic, but we got the result’, said the strategy director. It was successful on 2 key objectives:

- Comprehensive strategy framework for a significant, long-term business issue

- Large, committed, multi-disciplinary team bought into the outputs and solutions

After the showcases, when solutions had been selected and agreed, smaller project teams were formed to implement the outputs. They operated using waterfall methods – the business wasn’t ready for ongoing Agile project teams. As before, the business was not ready for ongoing Agile teams – people didn’t feel able from both capability and capacity to commit to ongoing Scrum teams.

Learnings from this phase

- There appeared to be a difference in learning impact for those on the programs as individuals versus those who joined as Teams supported each other, increasing their chances of applying what they learned. Intact teams, with leader involvement matter in embedding new ways of working.

- Virtual learning across different countries seemed good for building collaboration, as people understand each other more and it develops cohesion and identity. But I observed if groups don’t work together regularly, it’s hard to consistently apply the concepts so the learning impact fades over time.

- Applying Agile tools on a harder project builds confidence. More stretching experiences seems to make people keener and more confident. They are more invested and committed – known as the commitment bias in psychology, outlined by Rober

- A key success factor in the Polish work was senior level sponsorship and involvement. Both the strategy director and the supply chain director were heavily involved and invested. This signaled the importance to others in the team, and their involvement allowed for quicker decision making.

- When to apply Agile became much clearer. We started to understand complex adaptive problems, as defined in Dave Snowden’s Cynefin model. The strategy team in Poland also labelled these problems as wicked and started to work with more emergent, experimental approaches.

What I would do differently

Focus the virtual training on intact, existing teams. Allow them to collaborate with other learners in other countries to allow collaboration, but apply the learning in their own local teams. Apply the learning to actual business problems in their own countries, endorsed and supported by their leaders.

3.3 Phase 3: Agile everywhere: driving adoption across the business

By August 2021, there was momentum behind Agile ways of working within the HR function in the company. Around 100 people had been trained or involved in sprints work. Catherine and Geraldine were optimistic about bringing this way of working to the whole business. They wanted to integrate Agile more formally into the overall long term company strategy [called Better 2030]. These behaviours would allow employees to adapt quicker to the changing environment and support the company to becoming a learning organisation.

A new regional transformation function had also been brought together. They focused on developing region-wide solutions to specific functional problems, such as a new online platform to improve customer service experience. We saw this function as the next area to adopt Agile ways of working after HR. The newly appointed transformation director wanted to speed up of project development and saw Agile ways of working as an accelerant – although he had no personal experience of Agile.

Together, Geraldine and myself developed a company-wide adoption plan. This was not a transformation plan, as the objective was not radical change. The transformation team were focused on specific, functional projects – our ambitions were to change the culture on a company-wide basis. Using an adapted version of the maturity curve from Neil Perkins’ digital Agile transformation work, we identified specific stages and plotted our place on the curve.

We chose this model because it seemed grounded in practice. Neil Perkins actively works with companies and it is based on his own experience. It fitted better with our adoption focus – it seemed achievable without having to dedicate huge resources and total senior leadership commitment. Bringing Agile to 1 or 2 functions like HR and Transformation felt possible and realistic. The ‘final’ stage, where teams and bigger groups could chose their own frameworks and ways of working under the Agile umbrella, suited the Asahi decentralised model well.

Our objective was to embed Agile ways of working across the whole business. Our strategy was to build capability in small groups within every country – teams led by advocates and experts, usually from the HR function. We would influence leaders at country level through coaching and success stories, and build momentum at ground level through community building and large scale online learning sessions.

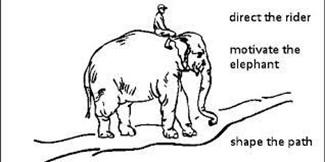

This was informed by a change model outlined in Switch: how to change things when change is hard by Chip and Dan Heath. Starting with the analogy of a man sitting on top of an elephant, it highlights the 3 types of interventions need to change behaviour in organisations.

The Rider is our logical, considered mind. We need to lay out a clear case for change, and be clear on what people need to do at a granular level (‘script the critical moves’).

The Elephant is our emotional, tribal side, often resistant to change. Here we focus on the emotion, on linking group identity to it, and making the change smaller and less intimidating.

The Path is about keeping momentum for change. Changing the environment, making progress visible, leveraging social power to encourage more people to join.

The plan had 4 key pillars:

- Leadership and Governance: vision, clear objectives, measured and monitored

- Community: creating advocates

- Training and coaching for leaders

- Guidelines and playbooks: develop a clear Agile ‘way’ of doing/being

Leadership and governance

We formed an Agile working group, with the transformation director and 5 HR directors, including the talent and learning director. Focus areas were identified from the annual employee survey:

- Speed of decision making

- Speed of idea to implementation

- Collaboration across teams

- Connecting individual work to company goals.

Measures were agreed and the role of the working group versus the community was established. The working group provided senior endorsement and structure for the whole adoption program.

This group made progress initially, creating a roadmap and objectives . A smaller group of 3 HR directors from the largest countries wanted to pause the program while they reshaped the vision and objectives. This work was not completed or presented, and the working group didn’t meet again after that decision.

Coaching and Training

Two training sessions for the executive committees of Poland and Romania were run to create momentum with leaders. By understanding the principles, senior leaders could create the conditions for Agile ways of working to grow. In Poland, this led to exec C=committee leaders participating actively in sprint work.

In the Netherlands, with my coaching support, the HR team created and implemented a hybrid working approach, catering for different user groups in their employees, led by an internal Scrum master.

Community

We set up and ran 3 Agile community online meet ups. Each meet up provided an opportunity for advocates and enthusiasts to meet and exchange ideas, and c.50 people attended each session. A key technique was showcased by an internal expert – kanban boards, user experience maps and retrospectives.

Guidelines

The company had a set of 5 existing corporate behaviours: Bold, Curious, Co-operative, Empowered and Committed. They were already embedded in the business. We developed an interactive set of toolkits linked specific Agile tools and techniques to pre-existing values and business habits, increasing likelihood of usage. They were available in the Transformation hub, an internal website.

Results from the program

It’s hard to draw concrete conclusions on the impact of the initiatives and the program overall. The coaching sessions produced some useful data and some success. In Poland, it supported the Executives’ active involvement in sprint work, which began with the large scale Scrum teams referenced in phase 2. In the Netherlands, it overdelivered on outputs and laid the ground for more Agile working in 2023. In Romania, the supply chain team wanted to use this way of working but the extreme workload left no slack for trying anything new – a classic ‘too busy to try ways of working to make us less busy’ trap.

Observations on the 4 pillars within the Adoption program

- Working group: Composition and member selection is key. Critically, the group lacked representation from Agile advocates below Director level in the business – it was top heavy, reflecting traditional corporate hierarchies. As John Kotter highlights in his change model, we needed a powerful guiding coalition. I would include more members from outside HR, and some enthusiasts from the community. I would also have proposed and championed a different change model – see below.

- The Community meetings were popular and successful and played the role of a Volunteer Army [Kotter]. – Attendance was voluntary, and many people from across markets and functions joined and interacted strongly. We didn’t follow up with measures to see whether the tools presented were being used – this is where Agile Champions by market would have helped.

- Training has a role, but how and when it is delivered is critical. It needs to be strongly tied to specific teams who apply it quickly to specific projects. This allows skill building and more importantly, growing confidence in their ability to run Agile projects.

- Assets, toolkits and playbooks are only used if people have the need, confidence and skills to apply them. The playbooks weren’t supported by an adoption plan so take-up has been limited.

4.0 Agile adoption: What I would do differently

Culture is sticky, take it into account ‘Culture eats strategy for breakfast’, said Peter Drucker, and prevailing culture is hard to change. The company culture was decentralised but hierarchical. Agile ways of working need shorter, faster decision-making approaches and some senior managers wanted to maintain high levels of control. High individual workloads also blocked full time sprint teams, this was a significant barrier.

Have the wind at your back: go with prevailing power structures, not against, and focus on removing obstacles. In a de-centralised company, focus efforts on country specific progress. The role of the regional team is to support and enable change. I knew this well from 10 years working as a Global Marketing lead in decentralised businesses, but didn’t apply it sufficiently well in my role as an external coach.

Shrink the change. Focus on smaller intact teams where there is enthusiasm at ground level and support at leader level. Establish Agile habits firmly, then move to adjacent groups. Only once a group has fully adopted a new product or behaviour, then target other groups. In marketing terms, this is called ‘building heat’ – creating smaller areas where the product dominates, made famous by Malcolm Gladwell in The Tipping Point.

Hand pick Agile champions in each market or group, and form them into a community. Work with their leaders to ensure they are supported. They are the core of change. The Polish business has a self-selected champion and has the highest Agile adoption across the region. Regional HR was focused on Agile behaviours, and the regional Transformation team was focused on applying Agile to projects. HR had a regional Agile champion, but the Transformation team had no champion and no expertise in Agile during the adoption program.

Bring these people together in person. We lacked in- person meetings during the program, partially due to Covid lockdowns. An annual gathering helps sustain commitment and enthusiasm in my experience with other communities.

Maintaining momentum in culture change is key. Early in the adoption program, the regional HR Director pointed out our main risk: losing momentum, which happened. We needed less control and more energy.

Capacity issues: Agile was often a secondary priority for people driving it. As workloads increased, Agile adoption went down their priorities. Even Board members said their operating businesses didn’t have capacity to try a new way of working. This applied to my own work as an external too: during the adoption process I led a large project inside the same company. Running an Agile project in a Waterfall business takes a lot of resourcefulness and energy – which impacts on adoption.

Goals and objectives: When working on a large project within this business, I learned the importance of linking specific product goals to the day-to-day work of a team. Connecting behaviour change measures back to company goals more tightly is something I would change – especially now knowing the Objectives and Key Results approach now.

My biggest personal learnings:

‘The more you know, the more you realise you don’t know’ Aristotle. I learned a lot during the work covered in this experience report. Appreciating and acknowledging how much I don’t know is perhaps the most important thing. Agile encompasses many tools and behaviours which I have yet to master. Knowing this keeps my ego in check, and drives my curiosity, and is one of the most transformative Agile behaviours for me.

‘To know and not to do is not yet to know’. Lao Tzu. Knowledge and expertise is situation specific – unless you consciously and explicitly decide to transfer and apply it. From many years of working in global roles, I was experienced in influencing teams in different companies without having positional power to leverage. Yet I didn’t make connections between those skills and Agile adoption and culture change as a coach. Just because you know something, doesn’t mean you’ll act that way in every situation.

‘No man is an island’ John Donne. I consulted many experts in my network throughout this time, and partnered with some on elements of the whole program – many of whom are listed below. From leadership coaches and organisational change leads to AgileHR experts and design thinkers, their help was invaluable. But starting again, I would involve a bigger team to increase our chances of success.

4. Acknowledgements

A very big thank you to Geraldine Percival and Catherine Sinclair for your support and partnership during these last 4 years, and for continuing to cultivate this mindset and way of working inside Asahi Europe & International. Your openness, generosity and honesty for sharing the unvarnished story with the world is a great model for people inside the business and across HR. Thanks as well to the many people within AE&I who believe in Agile and want to apply it more. Big thanks to Natal Dank for her insights and partnerships over the last 5 years. A shout out to Rahul Bhattachraya (Agile Atelier) for the Product coaching support. Thanks to my kind and supportive wife for proof reading. Lastly, thanks for my shepherd, Niels Harre, for your sharp observations and encouragement throughout – both an enjoyable experience a desire to constantly make it better – real kaizen!

REFERENCES

Dank, N & Hellstrom, R “AgileHR: Deliver value in a changing world of work ” Kogan Page, 2020

Cialdini, R “Influence: the psychology of persuasion” Harper business, 2006

Perkins, N & Abraham P, “Building the Agile business through digital transformation” Kogan Page, 2017

Heath, C & Heath, D “Switch: how to change things when change is hard” Crown business, 2011

Kotter, J “Leading change” Harvard Business Review Press, 2012

Snowden, D “Cynefin model” https://thecynefin.co/about-us/about-cynefin-framework/