Overcoming One-Size-Fits-All Budgeting: Fitting Your Budgeting Approach to the Agility of Your Business

This entry was written as part of the Supporting Agile Adoption program, an Agile Alliance initiative dedicated to supporting organizations and their people to become more Agile.

Agile transformations can easily be disrupted by a traditional non-Agile budgeting approach that contradicts the flexibility, adaptability, responsiveness, and nimbleness required by Agility.

For example, while your product development organization is making progress learning and applying Agile ways of working and slowly developing a mindset of Agility, the mindset and actual handling of financials remains the same: Budgets are still based on the paradigm of predictability and, therefore, conflict with the capability of embracing change and enabling plans to be adapted as you learn.

A journey toward Agility is usually triggered by a business environment that demands fast adaptability. Due to the growing complexity and resulting unpredictability in the business, companies try to find a different approach to stay profitable sustainably. Agile ways of working are promising to achieve this.

Often, however, we see that during the transition to an Agile operating model, the handling of financial resources is not adapted in the same way. The old procedure of forecasting (predicting the financial resources needed), budgeting, resource allocation, and tracking (how do we deviate from the forecast?) continue no matter the Agile journey.

For example, a development team that is implementing a new product feature cannot predict exactly when they will be finished and thus how much effort and money will be needed. If the team takes customer focus seriously, it will allow the customer to gradually develop their understanding of what they really need, both in terms of features and in being market-ready.

Change is accepted as an integral part of the creation and delivery process. However, controllers often ask for an exact amount of money needed and push the team for an estimate that aligns with the controller’s expectations. Eventually, of course, the team provides an estimate although they don’t feel good about it, as there is still a lot of uncertainty.

Later, the controller does a monthly follow-up, maybe challenging the team if the expectations are not met. Being confronted with, “You are not following the plan!” the team might become hesitant to discuss facts transparently. They start to perceive the funding and tracking discussion as a waste of their time. Moreover, by pushing the wrong discussion (characterized by a change-avoidance mindset), the controller will prevent the ability to adapt to the actual (changed) business needs. Instead of discussing how to adapt to the customers’ changing needs and any insight that has been gained, the discussion is about following the pre-defined plan, which is the wrong discussion.

Ask Different Questions

So, should we give up budgeting altogether? No, of course not. Any organization requires approaches to distribute the limited funds available so that an operation stays afloat AND innovation is stimulated.

Our challenge is that often the wrong questions are asked, especially to teams working on innovations. Asking what specific development work will cost is not the answer. Instead, the questions should be, “What is the business’ potential, and, consequently, how much are we willing to invest? Both questions should be answered jointly by the “idea donors” as well as the “gold owners.”

Additional Questions to Ask

More informative questions to ask are the following:

- How predictable is your business potential?

- How high is the risk of the endeavor?

- How much previous knowledge do we have about the endeavor?

- Can you compare this new endeavor with anything you have done before?

- Has your customer clearly articulated what they need?

- How many surprises have you encountered while investigating the business?

Budgeting Depends on Context

We also need to understand that budgeting depends on context. Unfortunately, however, we often treat everything in the same way when it comes to budgeting.

The first step in the right direction is to fully understand the different endeavors and their requirements. These endeavors could be the development of a new product or service, how to to deal with travel expenses, costs for education and learning, or selling a commodity versus researching an innovative idea, to name a few.

The next step is deciding how these endeavors can best be supported financially.

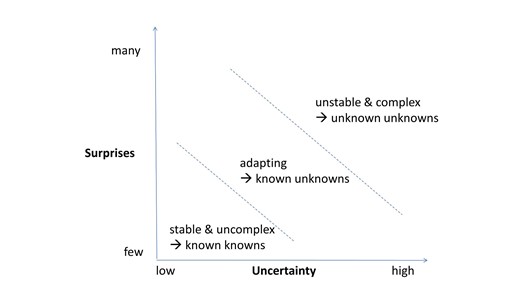

Understanding the context of your endeavor means setting possible surprises and the uncertainty you are experiencing working on your endeavor in relation to each other. The figure below shows this relationship by a so-called Landscape Diagram. This diagram has been developed by Holladay and Quade from Human Systems Dynamics and is based on Ralph Stacey’s work.

Contextual Variations for Systems

Contextual Variations for Systems

The “Stable and Uncomplex” Space

If your endeavor is in the “stable and uncomplex” space, meaning you do know what is going on (or, in other words, there are “known knowns” only), a classic budgeting approach will work fine for you because you have so much knowledge, experience, and stability that you can predict and forecast very well.

The “Unstable and Complex” Space

If your endeavor in the opposite space, that is the “unstable and complex” space, then budgeting is more effective by taking a venture capital approach. There are so many “unknown unknowns,“ so many surprises as well as so much uncertainty that you can’t forecast or even set a stable target. A venture capital approach means you believe and bet on the potential of an idea, but as you want to manage risk, you invest a little to learn and then invest more only if you see that value is created either in terms of what you’ve learned or even profitability.

So, for example, let’s say you believe there may be business potential, but you need to find out if your belief is justified by seeing results. In this case you would invest X-amount in order to see a result in Y-time so as to uncover some of the “unknown unknowns,” giving you more “known unknowns” or even “known knowns.” By running and funding many small experiments, you will understand the business potential better, and once you do, you can change the budgeting approach to a more flexible one.

The “Adapting” Space

In the “adapting” space, however, you can start exploiting the knowledge you have already built up. You are aware of many “known unknowns” and therefore are able to mitigate, set a target, and create a forecast while still leaving the door open to surprises.

In this context, a good practice is to separate the purpose of the budget in terms of target, forecast, and resource allocation as suggested by Beyond Budgeting. Understanding these different purposes allows you to then adapt your budgeting approach according to the contextual relevance. Some examples:

- Trust and Transparency: For things like travel expenses, office supplies, or other equipment, you should trust your employees to spend the money wisely (as you do when they take responsibility for a project). In addition, ask them to make their spending transparent by, for example, recording it on an intranet.

- Burn Rate: Decide on a budget upfront and allow everyone to operate with full autonomy within this budget.

- Unit Cost Targets: Allow expenses to increase as long as productivity increases as well.

- Benchmarked Targets: Limit expenses only by a comparable unit, e.g., last year’s spending, competitor’s spending, etc.

- Profit Targets: As long as the expenses help you to maximize profit, there is no need to interfere.

In an “adapting” context, let’s say you have a vision for a product feature, but you are not exactly sure of all the functionality it needs in order to add value. So you look at your current understanding of the functions and assemble an initial set of functions to be developed (aka MVP) and get funding for this.

Once the MVP is delivered, you have learned more and received customer feedback. You’ve become more certain about other functions that will add value, and so the next couple of functions will receive funding. And on it goes.

In this way, funding is done gradually as you learn, not upfront for the whole product feature.

Your Approach to Budgeting Needs to be Agile

In a business world that demands higher delivery speed, it pays to cast a critical eye on how your budgeting processes best enable your value creation.

Traditional budgeting is not “wrong.” It just does not fit all situations. Context is your key driver when it comes to defining the most effective budgeting approach.

The need for budgetary control is real, but that need should serve your requirement for innovation and a healthy workforce, not stifle or restrict it.

If your attempt to become Agile is serious, you have to be aware that there is no one single way for budgeting.

Your budgeting approach has to be flexible, adaptive, responsive, and nimble. This is done by taking the context of your various endeavors into account. The context will then decide for each of the endeavors which approach is best: a traditional approach, or venture capital approach, or an adaptive approach.